⚠️ Spoiler Alert ⚠️ This article explores Seasons 1–6 of Hulu's television adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale, along with its literary sequel, The Testaments.

Aunt Lydia is one of the most complex and polarising characters in The Handmaid’s Tale - Margaret Atwood’s original novel, it's sequel The Testaments, and in Hulu's television adaptation.

Lydia serves as a powerful lens through which themes of power, indoctrination, trauma, and redemption are explored. Unlike characters who resist the regime openly, Aunt Lydia’s disengagement is slow, covert, calculated, and layered with contradictions—driven as much by disillusionment and personal betrayal as by any ideological awakening.

Yes —Aunt Lydia’s story is, in the end, one of disengagement.

Claims that Aunt Lydia’s arc in Season 6 depict her radicalisation toward rebellion and Mayday miss the mark entirely. This isn’t radicalisation—it’s a complex narrative of complicity under coercion, survival, and slow, conflicted disengagement and resistance against a system she helped build and uphold. To call it radicalisation is not just inaccurate—it oversimplifies one of the show’s most complex characters and completely overlooks the way she disengages from within.

Aunt Lydia is case study in how ideology takes root, how people can rationalise complicity, and poses the question of whether redemption is truly possible after participating in oppressive systems.

Her journey forces audiences to confront uncomfortable questions about moral compromise, accountability, and change.

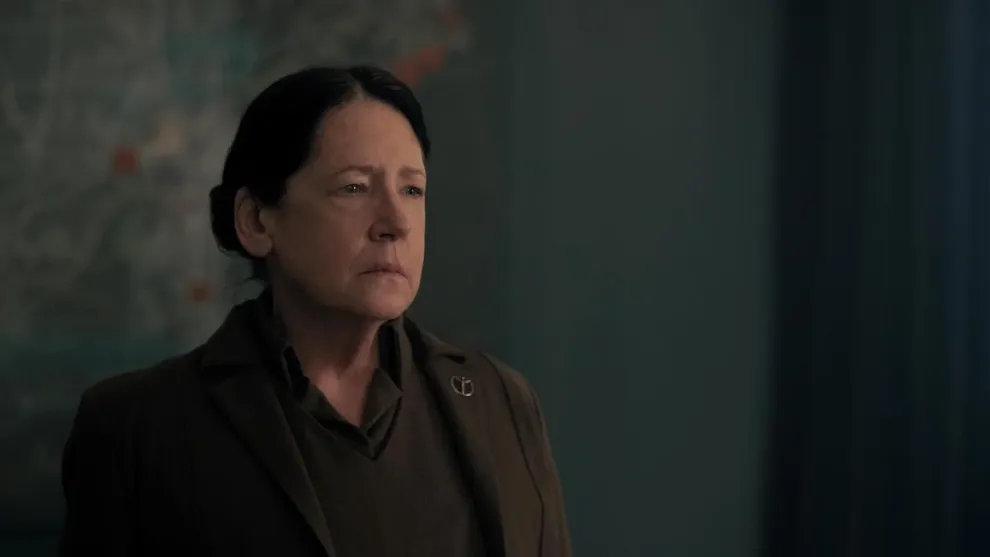

Lydia

In The Testaments, Lydia's backstory reveals she was not a true believer from the outset.

Before Gilead, Lydia was a family court judge, known for her strong morals and commitment to justice, particularly for vulnerable women and children. She was a school teacher for a short time, before returning to law. Her romantic life, what little we know of it, was marked by disappointment and a deep sense of unfulfilment. When Gilead rises to power, she is arrested and imprisoned alongside her colleagues and other professional women. After enduring extreme conditions in detention - humiliation, brutality, solitary confinement, starvation -and being forced to witness and later participate in an execution, she is offered a choice: collaborate or die.

Once she chooses collaboration (in so far as one can under coercive control), Lydia begins to internalise aspects of Gilead’s ideology, her longevity precariously reliant on continuously proving her loyalty - and zealotry. To do this, she starts to justify her role as necessary for the greater good, believing she can shape outcomes from the inside, framing her work as a form of protection for women in a regime where they are regarded as nothing more than property. Aunt Lydia comes to see herself not only as a necessary component of Gilead but as a moral, protective force within it. Far from being a behavioural anomaly, the rationalisation we see in Lydia's story is also often observed within those caught in authoritarian regimes.

Aunt Lydia

Over time as an Aunt, Lydia gains power, autonomy, and authority within Gilead. She is strategic about this from the outset, acutely aware that even in her privileged role as an Aunt - one of the few women allowed to read, write, and have freedom of movement, albeit within strict boundaries - her survival relied on her ability to navigate the complex political dynamics between the male and female spheres of Gilead, while maintaining dominance and control over a group of women (mostly Aunts, but Wives and Handmaids as well) fractured by mistrust and self-interest. The psychological seduction of influence and control plays a role here, which she admits in The Testaments.

Aunt Lydia is also partially driven by the prestige and privilege she gains in a world that otherwise erases women in public life.

The initial trauma of her coerced capitulation, combined with exposure to systemic violence, desensitises her. Over time, she becomes capable of enforcing brutal punishments, believing they are justified or even necessary in comparison to the alternatives. Her personal trauma is not processed—it is channelled. Lydia's almost constant internal, and often external, dialogue is one of justifying her actions to protect the women under her control from a fate far worse than that of a Handmaid.

Later in The Testaments (and by the end of the Hulu television series), she begins to confront the illusions she had long upheld about the extent of protection she could offer those under her care—the weight of their suffering eventually becoming too great a burden to continue bearing in complicity.

This marks the beginning of her ideological disengagement from Gilead, but even then she isn't driven purely by moral clarity—it’s part strategy, part revenge, and part legacy.

Aunt Lydia’s radicalisation wasn’t fanatical. It was coerced and traumatic.

Lydia radicalised out of necessity in Gilead. Her journey shows that radicalisation can occur through systems of power, not just through charismatic preachers or online propaganda. She is a chilling example of how good intentions, when manipulated by fear, control, and authoritarianism, can lead to deeply destructive outcomes.

Disengagement is complex.

Aunt Lydia’s disengagement from Gilead is a masterclass in slow, strategic resistance.

She's a woman who has played the long game - over decades.

Which should come as no surprise—what else would you expect from a lawyer and former family court judge? Lydia is sharply intelligent and strategically minded. Her legal background equipped her with tools and instincts that allowed her not only to endure Gilead, but to navigate, survive and , ultimately, help destroy it - with calculated precision.

Her disengagement takes shape not through protest, but through secrecy and subversion. As documented within the The Testaments under The Ardua Hall Holograph, Lydia continues to perform her role as an Aunt, maintaining her position of authority within the Aunt hierarchy, and appear loyal—all while carefully laying the groundwork to bring down the system she was a co-chief architect of. She begins secretly documenting Gilead’s abuses and working to dismantle the regime from within.

However, her disengagement is not pure or easily redemptive. Lydia’s strategy is effective because it weaponises proximity to power but her motivations are mixed: power, guilt, survival, and justice all play a role.

This form of disengagement is often overlooked in public discourse, which tends to valorise overt defiance while skipping over the deeply personal, emotional complexity of each situation.

In the end, perhaps the most unsettling question Aunt Lydia’s story forces us to ask of ourselves is this:

'Before you sit in judgement, how would you behave in Gilead?' ~ Sunday Telegraph